Showcase Filmmaker Spotlight: Robert Jaffe

Showcase Filmmaker Spotlight: Robert Jaffe

By Travis Trew, Programming Associate

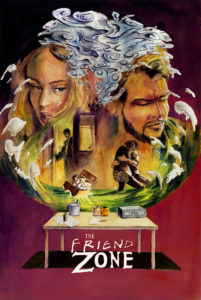

The self-described “living embodiment of Philadelphia,” Robert Jaffe has been making films since he was 16, and has been a fixture of the Philly film scene for several years. Currently at work on his graduate thesis project at Temple University (a very personal documentary about his relationship with his estranged father), Jaffe took the time to talk to PFS about his short film The Friend Zone, which will screen as part of Philly Film Showcase on Friday, May 5. Conceived as an unconventional blend of psychological horror and comedy, the film focuses on artist Lynne (Emilie Krause), who finds herself on both sides of the dreaded “friend zone” over the course of one disastrous night. Stinging from a rejection by her friend Jeff (Evan Raines), Lynne looks for consolation from David (Grant Struble), only to end up fighting off his unwanted advances. Seeking to mend things with Jeff, Lynne ends up in a confrontation with his justifiably angry girlfriend Marie (Samantha Lyn Parry). Jaffe finds surprising psychological insight in these everyday romantic foibles, resulting in a kind of emotional reckoning for his characters that lays bare the all-too-human failure of people to effectively relate to one another.

PFS: What was the origin of the idea for The Friend Zone?

Robert: It was a song. When I started making The Friend Zone I had been in the process of making a short film every few months. The Friend Zone is the first time that I really wanted to take my time to get the film the way I wanted it to be. It was born in a scene analysis class. It came from me repeatedly listening to the Arctic Monkeys song “I Wanna Be Yours.” I just kept listening to it over and over. It’s a really beautiful, romantic song. But it also is very much a “friend zone” song. It’s all about how this dude wants to be an object for this person. And I always found that ironic. The idea that “I want to be your object” is really about objectifying the other person. When I had that conclusion I started building the whole film around that song: laying in visuals that are found in music. I got far away from the song eventually, but it was always a foundational thing that inspired me in this direction.

PFS: What’s your take on the concept of the “friend zone?”

Robert: The “friend zone” is this thing where you like somebody and you tell them you like them, and then that person is like “I don’t have the same feelings for you, but let’s just continue pretending to be friends and pretend that this conversation didn’t happen.” And you’re both like “Great, we’ll do that.” But then for some reason the relationship goes horribly from there. The “friend zone” isn’t a thing that somebody does to somebody else, it’s when two people agree to a lie. I’m always going to be fascinated by the subject of cognitive dissonance and our capacity to blind ourselves to truths so that we can continue doing exactly what we’ve been doing.

PFS: Was it always your intention to have the main character be both in the “friend zone” and also an object of unrequited affection?

Robert: In the first draft there was no Jeff character. In the second draft there was an immediate switch-up. The first draft was very much the story that you see between David and Lynne, without Jeff. And it’s just a cliché. I think that showing that Lynne is in the “friend zone” too adds a lot more nuance to it. It’s not saying the “friend zone” is what happens when a guy likes a girl; the “friend zone” is what happens when two people agree to a lie in a relationship. And that’s it. The gender is meaningless. It’s about cognitive dissonance and our capacity to lie to ourselves. It wasn’t the first thing that I thought of but I quickly realized that it was a necessity for the story to work. It’s about our own ability to not see the things that we’re doing.

PFS: Even though the “friend zone” can go both ways in terms of gender, there’s a clear difference between the way David’s advances toward Lynne are handled vs. when Lynne does something similar to Jeff. Were the gendered aspects of the “friend zone” on your mind as you made the film?

Robert: A big thing for me was exploring the connection between what the “friend zone” is and what rape culture is. They’re both about entitlement and “I take you.” They’re both about control. So, yeah, I definitely thought about that. I can’t help but look at the differences between when Lynne aggressively kisses Jeff and when David aggressively kisses Lynne. Those are two very similar situations, in a way, that go radically different because of those gender issues. Tied into gender is autonomy, size, and respecting boundaries. You can see that there are lots of differences between how the David situation goes down and the Jeff situation. I still think they’re both fucked up. I don’t think it’s OK that Lynne forced herself on Jeff after she told her no. She should have respected that boundary and she didn’t. But it’s amazing how much farther David goes. Lynne takes the time to explain to David what she’s feeling, she’s very apologetic, she couldn’t be clearer! And he still rejects her words because he’s still going off of this fantasy in his mind. I don’t know if this is a gender thing in my mind or if it’s about how powerful cognitive dissonance can be in the pursuit of getting what you want.

PFS: What was the process of working with the actors like? Was there any improvisation?

Robert: The film itself doesn’t have a lot of improvisation in it, but we did a lot of improvisation beforehand, and a lot of play. Especially between Evan Raines and Emilie Krause, who play Jeff and Lynne, respectively. We went down to First Friday with a camera and we just had them meet up with each other and have a kind of impromptu date. It was a way for them to just be together and work on flirtation and establish a relationship. I worked that pretty hard. I did chemistry reads. When I did the original round of casting, I ended up finding Lynne first and then casting the Jeff that worked best with her.

PFS: We see a lot of the characters’ art in the film. What’s the significance of having Lynne and David be artists?

PFS: We see a lot of the characters’ art in the film. What’s the significance of having Lynne and David be artists?

Robert: I don’t think that I want to make it any more explicit than it is, but I do think that there’s something to the idea of living in fantasy and how easy it is to live in fantasy as artists. But at the end of the day I look at Marie and Jeff, and I see them both as living in fantasy too and I don’t think of them as artists. So, I guess my thinking is that regardless of whether you’re living in some kind of magical, art-filled universe or you’re living in a sober, white-walled, boring life, you’re still going to be dealing with the same kinds of dissonance. You’re still going to be using self-justification. And the idea of constructing a fantasy reality as being for people that are lofty and off the ground – I’m rejecting that. I think that regardless of whether or not you’re an artist or you’re an accountant, chances are you have some fantasies that you live out day to day in order to maintain your existence.

PFS: The title is obviously an allusion to The Twilight Zone, and the film takes some surprising turns in terms of genre. Did you set out to play with genre?

Robert: Yeah, absolutely. I allow this to be called a drama at this point because that’s what most people call it. But when I was writing I thought of it as a “psychological horror-comedy.” The title looks like The Twilight Zone, but it’s actually a combination of The Twilight Zone and Friends logos. Did you know that Friends invented the phrase “the friend zone?”

PFS: No, but that’s fascinating.

Robert: It is. In terms of genre blending, if you think of this as a blend of Friends and The Twilight Zone, that kind of works. Because it’s about people who think, “Oh, this is not a big deal, everything is cool.” And then underneath it all there’s this growing horror. The moment that David is giving Lynne the mix tape, that’s not really played for horror per se, but in my mind when you’re watching her face and you see her doing the calculations of how she’s going to get out of this moment, that’s a little horrifying.

PFS: What was the significance of the aside about the “Plastic Island of the Pacific?”

Robert: Ah, the Plastic Island of the Pacific. So I’m working on the trailer right now, which has a monologue about the Plastic Island of the Pacific that got cut from the film itself. There’s a lot of significance to the Plastic Island of the Pacific. Lynne’s monologue explains how people think of the Plastic Island of the Pacific, and they think of that as a literal thing. And it’s not. The plastic is melted down into bits, so you can’t really even see it anymore. So I think of that as a metaphor for these “friend zone” relationships. It doesn’t look like there’s a problem, but it doesn’t really address the greater issues or the long-term ramifications of the thing. We have a capacity to ignore things at our own peril, and the Plastic Island of the Pacific is certainly that. I shot this movie back in 2015, and it feels weirdly more relevant in this post-truth universe.

Friend Zone will screen on Friday, May 5th at the Prince Theater’s Black Box as part of Philly Film Showcase, an exhibition supporting new work by talented, up-and-coming local filmmakers.